The word ‘cabaret’ conjures forth cafés and burlesque performers, song and dance, food and wine, black cats, green fairies, and Bohemianism. And the word has been used in Louisiana and New Orleans as long as the French language has been spoken there. A sounding of historical texts and newspapers bears out this fact. The word has been used confidently by historians, especially those of jazz and prostitution in New Orleans, to designate a certain thing in a certain place, the Storyville cabaret, a house of wine, song, and prostitution, ultimately prostitution. But the history of the word ‘cabaret’ in New Orleans and that which it designated is complicated and unclear.

In the 1800s cabarets in New Orleans were a confused kind of business based upon the liquor trade. Newspaper accounts equated cabarets with ‘grog shops’ and only made reference to the numerous murders that took place there and their illegal sale of liquor to slaves. Licensing laws also related them to ‘grog shops’ and related musical performance rather to cafés and dance halls. The Orleanian cabaret, mostly located around the French Quarter, had an ill reputation and retained it throughout the nineteenth century. ‘The cabaret was a species of grogery, dram shop, gambling house and “fence” or depot for stolen goods, all combined’ (New Orleans As It Was (1896).) Orleanian cabarets of the nineteenth century were rarely, and not necessarily, related to musical performance.

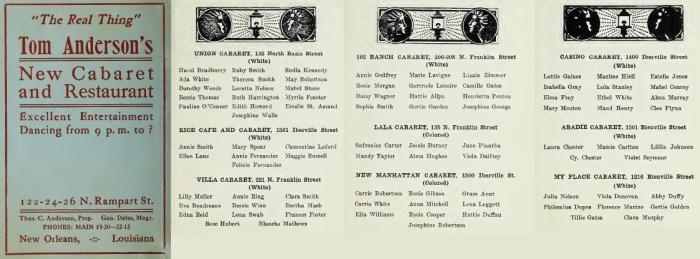

When the Blue Book, the manual of the restricted district, was published in 1906, it listed three cabarets, the Fewclothes cabaret, the Shoto cabaret, and Abadie’s. When a new edition of the Blue Book appeared in 1912, cabarets had suddenly multiplied. The reason was that in the intervening time a national enthusiasm for cabaret had radiated out from Broadway and had become a very serious business proposition. But this Broadway cabaret was a very different kind of thing to the Orleanian cabaret of the nineteenth century, and Broadway was very different kind of thing when compared to Storyviille.

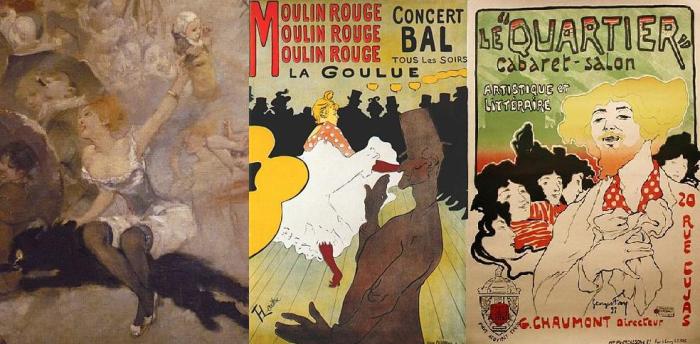

The word ‘cabaret’ was infrequently used in the United States, outside of Louisiana, until the 1910s. It was a word imported from France and was used to describe an entertainment environment modelled upon that which evolved from Rodolphe Salis’ Le Chat Noir cabaret established in Paris in 1881. Le Chat Noir was established by Salis as a saloon for the artists of the Latin Quarter of Paris and it soon gained a reputation as a place for art and performance, for Bohemianism as Henri Murger had defined it. Before Le Chat Noir, the cabarets of France had much the same reputation as those of New Orleans. As one journalist remarked, before Le Chat Noir the word ‘cabaret…was applied to little drinking places which were found in many quarters of Paris…[and] did not picture anything particularly pleasant to the French mind’ (The Sun Feb 23 1913 p12.) Soon after the fame of Le Chat Noir, French cabaret gained the weight of the Moulin Rouge and it was ever after transfigured.

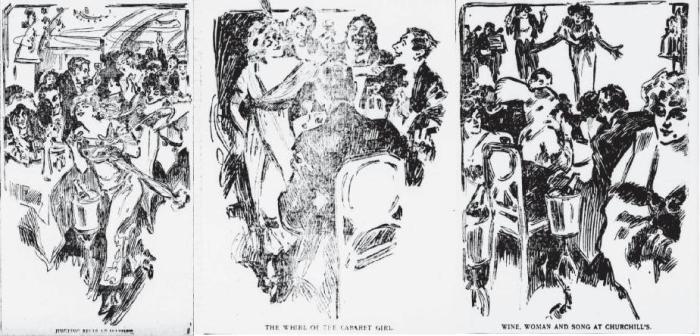

Newspaper accounts of Le Chat Noir appeared in the US as early as 1885 but the enthusiasm for cabaret that erupted in France took much longer to establish itself as an American business proposition. In 1913, the year American press gave great attention to Broadway cabaret, a journalist remarked that Broadway cabaret was ‘a new feature of the amusement business…hardly three years old…[that] has attained great proportions…[and has] become as necessary to the night restaurant as a reputation for sufficient lobster or tender fillets mignons’ (The Sun Feb 23 1913 p12.) The Broadway concept of cabaret that sparked off the national enthusiasm in practice was basically an eatery with entertainment wherein the performers mingled with the diners. This kind of cabaret spread to San Francisco and Chicago and became a circuit for vaudeville and burlesque performers. It grew to such a scale as to become a special target for prohibitionists and a consideration for increased taxes by the Treasury.

Back in New Orleans, the national enthusiasm for cabaret had its influence upon the dismal Orleanian cabaret. After all, the Crescent City wasn’t the ends of the earth and its businessmen read the papers and theatrical publications such as the New York Clipper and Variety. Cabarets proliferated, not only in Storyville, but across the tracks of Rampart Street in an area of the French Quarter that became known as the Tango Belt and which ran in length from Canal Street to St. Louis and in width from Dauphine Street to Rampart. Many theatres and cafés changed their names to include ‘cabaret’ and the focus of the Orleanian cabaret now, as in New York, became musical performance. Cabaret singers and dancers were drafted in from New York, Chicago and San Francisco, and many early homegrown jazz soloists and bands were nurtured in the cabarets of New Orleans, King Oliver, Louis Armstrong, Pops Foster and Jelly Roll Morton to name the barest few.

All strata of society in New Orleans could enjoy cabaret performance of some description. The wealthy went to venues like the Grunewald’s cave and the sporting-types went to the cabarets of Storyville and the Tango belt, to such joints as Pete Lala’s cabaret (formerly café) and the Haymarket theatre. Variety in 1915 listed the Greenwall, the Haymarket, the Raleigh, Turf, Frisco, Brooks’, the Cadillac, the San Souci, Toro’s, and Anderson’s as the legitimate cabarets of New Orleans. The Blue Book of the restricted district listed many others.

Variety in 1913 warned performers to ‘investigate carefully before signing contracts’ as ‘many of the cabarets in New Orleans are situated in a very tough district’ (Variety May 1913 p.27.) Some Broadway agents failed to heed the warnings and made bookings for Storyville cabarets. When their clients, female singers and dancers, realized where they had been booked, they complained to the federal authorities. The Broadway agents were subsequently prosecuted under the Mann Act and charged with white slavery.

Some joints that jumped on the cabaret bandwagon, such as the Green Tree cabaret, were simply roughhouse. The origins of the Green Tree lay way back in the nineteenth century. It had formerly been regarded as something of a saloon, lodging house, and dance hall, and throughout the nineteenth century the Green Tree had maintained a reputation as the house of most ill repute in New Orleans. That took some doing. It was frequented for a time by a violent and chaotic wharf rat gang known as the Live Oak boys. Murders occurred in the Green Tree frequently. Prostitution was a given. In the 1910s it re-styled itself as a cabaret. The last proprietor, Alexander Richard Holzscheiter, closed the Green Tree of his own volition in 1915 and reportedly left these words pinned to the door: ‘This has been called the most disreputable place in New Orleans. No longer will I associate with the men and women who frequented it. I lose all, but I will live among clean people and make my living honestly’ (The Hartford Herald Oct 27 1915.)

Café or cabaret. What’s in a name? Much and nothing at all in its rapid utterance. Similar setups to the Broadway cabaret already existed in New Orleans before the 1910s but they were usually regarded as cafés. Then there was the rathskeller, a German restaurant with entertainment. Kolb’s rathskeller operated on St. Charles near the Orpheum theatre. The difference between café, rathskeller, and cabaret was simply that of being the product of an entertainment fad spread by the American media of the 1910s. This cabaret fad transfigured the Orleanian cabaret and gave it vitality, and the cabarets of Storyville and the Tango Belt are weaker things when not considered in this context. In turn the cabarets of New Orleans transfigured American cabaret, for they contributed the one most distinct and enduring feature of American cabaret of the 1910s, jazz and its associated dancing. Indeed, one of the apocryphal origins of jazz that circulated in newspapers of the 1910s was that it was the discovery of a cabaret man in New Orleans. This cabaret man was presumably Joe Frisco the famous jazz dancer.